Journal of Indonesian Society, Volume 48 No. 1 Year 2022 journal homepage: http://jmi.ipsk.lipi.go.id

CONTROL AND PARALYZATION OF PAPUA'S POLITICAL RESISTANCE 'THE QUESTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS WILL BE DEALT WITH LATER'

Paralyzing Papuan Political Resistance, Human Rights Regulated from Behind

Theo van den Broek

SKP-KC Fransiscans Papua Email:theovdb44@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

In this reflection, we outline the characteristics of the societal situation in Papua at the end of 2022. The current situation is the result ofthe 'security approach strategy' implemented by the Indonesian Government over the past 3 ½ years. The government hoped that with the 'security approach' the conflict in Papua could be resolved. De facto, what has been achieved: the application of this strategy has resulted in the opposite situation, namely: the conflict has not been resolved, but has become much more complex and difficult to overcome. The security approach strategy was accompanied by an escalation of violence that not only threatened the physical lives of many citizens, but alsohad a very negative impact on several sectors of society (including the rule of law sector, the freedom of expression and assembly sector, the democracy sector, and the population sector). After three and a half years of favoring the security approach, the Papuan people, in particular the indigenous Papuan people, feel that they have been ushered into a dead end. An atmosphere in which there is no longer a bright spot for a resolution of their problems with dignity. In order to pave the way for a good and peaceful resolution of the problem, we need to [1] eliminate the negative impact of the 3 ½ years of policy, and [2] the willingness of all parties to show a true 'political will' and open themselves to dialogue, including discussion of the political aspects which are actually the main root of the problem in Papua.

Keywords: Rule, Papua, human rights, rule of law, state of power

INTRODUCTION

We were asked to write an annual reflection on the situation in Papua in the year 2022, early 2023. In this reflection, however, we have tended to broaden the timeframe of the

reflected period, becoming 2019-2022. The reason: the situation during 2022 is difficult to understand if it is not linked to several developments during 2019 to 2021. In our reflection, a pattern emerges that suggests that over the past four years a 'grand design for a strategy of strengthening power' has been systematically implemented.

The starting point was the actions of the West Papua National Liberation Army (TPNPB) in late 2018 (the killing of 16 road workers in the Nduga region) and the 'racial riots' that began with racial incidents in Java (Surabaya, Malang, Semarang) where Papuans were declared 'monkeys' in August 2019. What followed was not a serious handling of the racial conflict - which is still quite alive in Indonesia - but a clearcut effort by the government to paralyze any political resistance in Papua.The core of the strategy: to take control of Papua as a whole and paralyze any political resistance in Papua.

A security approach that does not shy away from the use of violence. 'Violence' is both 'physical violence' and 'violence in the juridical legal sector'. The question, to what extent can a security approach with violence be applied, is indirectlyanswered through the expression of the Speaker of the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR), Bambang Soesatyo, namely"the security forces deploy full force and crush the armed criminal groups". According to him, the security forces do not need to hesitate and human rights matters can be discussed later ('Chairman of the MPR Tumpas Habisabis', April 26, 2021). This is what he said when commenting on the killing of the Papua BIN chief (25/4/2021) who was killed in an attack by TPNPB.

'PENTAGONAL VIOLENCE'

Accompanying the 'strategy of control' is the escalation of the use of violence. In a report by the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPAC) (IPAC, July 13, 2022). it was noted that in the period 2010-2017 violent incidents in Papua amounted to an average of 11 incidents per year. In the period 2018-2021 this number became an average of 52 per year. The number of victims increased dramatically: of the 320 people killed between 2010 and 2021, 211

(66%) were in 2018-2021. Of the 211 killed, 52 were TNI-Polri members, 34 were TPNPB members, while 125 were ordinary civilians. In addition to the dead, there were a large number of people injured, and no less than 60,000

ordinary people left their homes because they no longer felt safe there due to ongoing military operations. Thus, there are 60,000 Papuans displaced in their own land.

The escalation of 'violent control' is not only found in the security sector. The Papuan people, especially the Indigenous Papuans (OAP), experience that the 'strategy of control accompanied by violence' actually affects all aspects of daily life in Papua. The community is entangled in a fivefold circle of 'mastery accompanied by violence'. 'Control-Violence' is felt in [1] the security sector, [2] the legal and juridical sector,

[3] institutional and democracy, [4] population, and [5] communication and information. In what follows, we will briefly elaborate on each of these five aspects.

[1] Mastery through Violence in the field of security

Since mid-2019 (racial crisis) Papua has been systematically and structurally flooded with TNI-Polri troops. Thousands of troops were deployed to Papua; an average of 1,000 personnel per month over the past three and a half years. At first they were concentrated in Timika, the center of the Kogabwilhan

III. The initial reason for deploying troops to Papua was the anti-racism protest movement. However, the number of troops sent and the speed with which they were sent were actually disproportionate to the problem of racial protests in the community. Moreover, the racial protest movement was initially for the most part peaceful; deploying the local police could have been sufficient. It was only at an advanced stage that the racial protest movement - for good reason - was used by 'unknown people' (and never investigated) to become anarchic. Specifically in Jayapura (August 29, 2019) and Wamena (September 23, 2019).

2019).

The impression is that the troops have long been prepared and are ready to be dispatched. Just waiting for the momentum. As if there was already a 'policy handbook' (or: strategy blueprint) and everything was neatly implemented by the Menkopolhukam, Wiranto, and the National Police Chief, Tito Karnavian.

Despite being deployed to Papua in relation to racial unrest, it was in December 2019 that confrontations with TPNPB began and/or were sought, and a series of conflict areas began to emerge. Initially the TNI-Polri sent troops to the Intan Jaya region, with the aim of 'ensuring public safety during the Christmas New Year celebrations'. Up until that point, Intan Jaya had no history of conflict. However, it turned out to be a conflict area starting in December 2019. Then the number of conflict areas continued to grow: Nduga, Puncak, Puncak Jaya, Yahukimo, Yalimo, Mimika, Bintang Mountains, Yapen Islands - all within Papua province - and the Tambrauw and Bintuni Bay regions in West Papua province. The emergence of conflict in certain areas is also inseparable from economic interests (access to natural resources) for certain parties, including the authorities (Rakhman, et al., 2021).

At first the non-organic troops were commanded from Jakarta. After General Andika Perkasa became Pangdam TNI the strategy changed slightly, until all troops deployed to Papua were included in the existing territorial structure in Papua. 1 Thus becoming 'organic troops', and getting closer to the community, so that it can show a more 'humanist' approach. This strategy is also supported by the regional expansion plan which will expand the territorial military structure through the creation of new provinces. Thus, the presence of large numbers of troops could become more permanent as they are designated for territorial assignments.

Meanwhile, mutual provocation between TPNPB and TNI-Polri continues. TPNPB declared war against the TNI-Polri and anyone associated with this strategy of control by the authorities. TPNPB also gave warnings to residents, in particular 'non-Papuans' who were in the conflict area to leave the battlefield. Casualties began to fall. Not only in direct armed contact between TPNPB and

1 Only one unit was excluded, viz: Operation Cartenz Damai Unit, which operated from Timika, and numbered 1,925 police officers and 101 TNI soldiers.

TNI-Polri, but also increasingly from among ordinary villagers. They became victims of both TPNPB aggression and TNI-Polri aggression, and the number of civilian casualties increasingly exceeded the number of casualties among TPNPB and TNI-Polri. Moreover, the atmosphere of armed conflict encourages people to leave their hometowns witheverything they own, houses, land, livestock, etc., to become refugees in a place of deprivation. The number of refugeeshas reached 60,000 in 2022.

[2] Control accompanied by violence in the legal and juridical field

This includes violence experienced through the arbitrary arrest of political resistance leaders. One example is thearrest of a number of political resistance leaders after racial protests. Without a proper investigation, they were arrested. At the time the National Police Chief, Tito Karnavian, stated that a list of all suspects was in his pocket, before a proper investigation was conducted. That was not the only time. Still today activist groups such as the KNPB are very easily accused of being the perpetrators of any 'incidents' without their involvement being proven. The result is actually tragic: for example in the Kisor Case (Sept 2021) all KNPB leaders in the Tambrauw-Sorong region were declared suspects andsubject to arrest. The style of 'arbitrariness' and 'criminalization' is quite evident. Especially if we look at the fate of around 80 Papuans who were declared 'treason suspects' after the anti-racial protest movement. In the eventual court process the judges needed to recognize that the 'treason suspects' had not actually been proven wrong. Nevertheless, they were given sentences. Sentenced to imprisonment of approximately the same length as the time they had been detained (approximately 8 to 11 months). By giving such a sentence, the court can avoid that the detainees can claim damages from the state for being detained without reasonable grounds ('The murky fate', November 21, 2022).

The 'legal and juridical violence' is also evident in the attitude of the police, the security forces, who do not give any space to activists who want to protest. The right to freedom of speech is completely disregarded, and the denial of that right has become standard for any 'peaceful assembly'. Any protest gathering will be forcibly dispersed. It is usually accompanied by the arrest of a number of people and the maiming of many more. Lately, this pattern of suppression has also been complemented by the use of tear gas as standard equipment. Meanwhile, the regulation stating that any peaceful protest only needs to be reported to the security forces is being ignored. According to the regulation, there is no need for a permit, just a report. The nuance in this is long gone and routinely any movement is 'denied a permit', to the point of being dispersed. The guaranteed right to freedom of opinion and the country's Constitution no longer apply in Papua.

'Legal and juridical violence' not only relates to freedom of expression, but, for example, also impacts on the recognition of indigenous peoples' 'traditional property rights' over their land, or the right to refuse investors entry to their territory or to resist land grabbing. Among other things, the passing of the "Omnibus Law" (Job Creation Law) is one of the means that legitimizes the easy use of 'legal and juridical violence' as referred to above. Thus, not only are the rights of indigenous peoples denied, but in fact indigenous peoples are deprived of their food security and right to life. The marginalization of indigenous peoples due to the priority given to 'investor rights' increasingly characterizes the style of development in Papua today. And even though the Constitutional Court has declared that the Job Creation Law is legally flawed to the point of being considered 'conditionally unconstitutional', the implementation of the Job Creation Law is still being carried out. In fact, recently (31/12) it was imposed again through a Government Regulation in Lieu of Law (Perppu) by the

President who himself violated the law (Akal bulus Perpu Omnibus,' January 8, 2023).2

'Control with violence' is also reflected in the handling of cases of human rights violations in Papua. Many cases are not followed up at all or are simply postponed. Meanwhile, cases of gross human rights violations that are handled, such as the Paniai case (2014), are treated as a kind of charade where justice is not sought but is grossly undermined. The Paniai case, which involved several perpetrators, identified by Komnas HAM, was tried with only one suspect, and this one was eventually acquitted as innocent! A tremendous blow, not only to the families of the victims of gross human rights violations, but also to anyone who still hopes that the state will ensure that the law is applied correctly and that justice is done. Slowly we in Papua are beginning to feel that Indonesia is no longer operating as a 'state of law', but as a'state of control'.

[3] Violent control of institutions and democracy

From 2020 onwards the 'strategy of control' began to be accompanied by 'administrative- institutional violence'. That is: administrative changes, specifically through the Special Autonomy (Otsus) Revision and the New Autonomous Region (DOB) Plan. Both Otsus Volume II and the DOBs were established by denying all forms of broad public participation, voice and protest. It is indeed very unusual how a 'legitimizing process of unilateral control' - the de facto DOB plan was decided by a handful of officials on September 11, 2020 - is slowly achieved through a 'power play' of a few powerful people ('Makhfud MD: Papua, 11 September 2020)

2 In relation to the issuance of the Perppu on the Job Creation Law, in an opinion published in Tempo magazine (January 8, 2023), it is described that such actions increasingly show that Indonesia is starting to apply 'autocratic legalism'. This term refers to the act of consolidating power through a number of methods that seem legal even though they essentially undermine democracy and the Constitution, including the limitation of power.

2020). Perhaps they are also being helped because politicians in the central government seem more preoccupied with the '2024 Presidential election' than with serious political issues in Papua.

In this process, all public protests against Otsus Volume II and the DOB Plan were rejected and dealt with with apparent violence. The entire legitimization process was carried out and accommodated without conducting a proper evaluation of the 20-year experience of Otsus. Even the Papuan People's Assembly (MRP) when they wanted to hold an evaluation meeting with the people to hear their opinions, the MRP was blocked by certain agencies supported by the authorities, so the evaluation meeting did not take place ('Indicated treason,' November 17, 2020).

Specifically in relation to the establishment of expansion programs, the authorities have also ignored the 'moratorium on expansion' since 2014. The moratorium exists because from an evaluation of all expansion programs in Indonesia it became clear that only 24% could be declared successful. 76% failed! So, the pattern of expansion needs to be rethought and produce a new concept of expansion so that it is more appropriate and potentially successful. In the current process of establishing DOBs in Papua, this warning has been completely ignored. Nor is it given the attention it deserves

- actually an absolute requirement - on preparatory studies, assessments of opportunities for independence and all sorts of factors that would determine the success or failure of the expansion. All these requirements were ignored and hastily dismissed by Commission II of the DPR RI. Instead, arguments that made perfect sense and that were presented by competent parties, such as academics, were ignored as if they were just 'annoying garbage'. 3

3 Compare for example all the data presented by Dr. Agus Sumule, when he took part in the discussion during the webinar organized by BRIN on 29December 2022. His PPT is titled DOBs in Papua: What the Statistics Say and Implications for the Future (agussumule@gmail.com). Based on the data

It is disturbing to realize that key policy patterns (Otsus and DOBs) can be established and legitimized without a proper evaluation of the 20 years of Otsus experience, and without following the guidelines for eligibility requirements for administrative units. In the case of Papua, apparently 'exceptions' were made without much thought, until the policywas simply enacted to suit 'certain political interests'. A style of state policy-making that contrasts sharply with the way policy-makers talk, where 'improving the welfare and progress of the Papuan people' is always raised as a top priority. Turns out: just cheap words.

Meanwhile, de facto, according to a phrase from Tito Karnavian, expansion is based on "BIN information" [BIN=National Intelligence Body]. Thus, expansion in Papua has only one goal: territorial control. This process of 'administrative violence' also shows that at the national level Indonesia's democratic spirit has greatly declined and institutions such as the DPR RI have lost their 'function as representatives of the people'. Everything is simply 'directed' towards the achievement of 'official legitimacy'.

Another impact of the 'violent control strategy' is the loss of space for local governments to set autonomous policies.With a dominant 'security approach', local governments cannot move without adapting their activities to the de facto policies set by the security forces. Moreover, the role of BIN in setting local strategies cannot be ignored. Then add the results of the Revision of the Special Autonomy Law. In Otsus Volume II, the autonomous space for regional governments has been significantly limited, aka meaningless (IPAC, 2021). Moreover, the Revision of the Special Autonomy Law is complemented by the establishment of a Steering Committee for the Acceleration of Special Autonomy for Papua, chaired by the Vice President, and with over 90% of its members from various ministries in Jakarta. The government in Papua only needs to receive instructions and ensure that the policies determined by Jakarta are followed.

official report on Education, Population and Poverty,

HDI, Provincial Fiscal Capacity, he pointed out that

a.l. "the marginalization of native Papuans will become

more intense It may even lead to creeping genocide". The plan

for new autonomy regions may not be realized...

As a result of these developments, local governments have increasingly shown a lethargic attitude of 'just waiting' and 'going along with the crowd'.

[4] control accompanied by violence in the field of population

According to the 2022 population census, the population in Papua reached a total of 5,437,779 people. Papua Province (old form) is 4,303,707 while West Papua Province (old form) is 1.134.068. Although data on the composition of the population in terms of 'indigenous Papuans' and 'non-indigenous Papuans' is not available, it is no secret that the number of Orang Asli Papua (OAP) has become a significant minority in their own land. It is also quite clear that most of the OAP population lives in the mountains and non-urban coastal areas. That is where the OAP population is still a clear majority. In contrast, in urban areas, the centers of government and trade, the demographic makeup has changed dramatically; that is where the OAP population is a very real minority. Cities such as Jayapura, Merauke, Sorong, Timika, Fakfak, Nabire clearly show a prominent plurality, where the percentage of the OAP population barely reaches between 20 and 30%.

This demographic change is the result of a migration of people from other parts of Indonesia. This migration flow was once actively encouraged (Suharto era: transmigration program) and then continued (spontaneous migration) and was never controlled. Its impact has been experienced for a long time, particularly in the fields of economy, trade and politics. These sectors are heavily dominated by migrants, and the presence of migrants also increasingly dominates government institutions. As just one indicator, compare the OAP quota with the non- OAP quota as members of the DPRP/D in a number of regions inPapua below (Table 1):

This means that all government policies in Papua are increasingly less determined by the 'voice of indigenous Papuans'. Repeatedly, attention is drawn to the pattern of development, which relies heavily on the flow of migrants, creating a marginalization of indigenous Papuans, both economically and politically. Moreover, the majority ofindigenous Papuans still live in areas that are known to be rich in natural resources, so that they are attractive to investors, traders and all those who seek their profits. It should be noted that it is precisely the areas that are rich in natural resources and at the same time the majority of the population of native Papuans during these last years have changed their status, namely: they have become conflict areas, and they are increasingly controlled by the security forces.

The impact of migration and this drastic change in demographic composition will receive a special boost through the creation program of four, five or six new provinces. The creation of new provinces will require all kinds of facilities, new construction and also a qualified workforce to fill all the seats in government. This reality will attract a huge number of migrants. There is no mechanism in place to control this influx of migrants and protect the rights of indigenous peoples. Thus, in terms of the marginalization of indigenous Papuans, the creation of a new DOB is a tremendous disaster. All policy makers in the central government can realize this consequence. De facto, such considerations were given no place in the process of enacting the 2022 DOB Law. For what reason?

[5] Mastery accompanied by violence in the field of communication and information

One factor that plays a major role in the pattern of developments in Papua is the extent to which proper information about what is happening in Papua is allowed to become known to the wider public. The general public in Indonesia generally does not know much about Papua. Only a little is known. And that 'little' is often colored by stereotypes such as

Table 1. Papuan DPRP membership by residency status

NO | DPR MEMBERSHIP NAME REGENCY/CITY | NUMBER OF MEMBERS | INDIGENOUS PEOPLE OFPAPUA | IMMIGRAN T |

1 | Sarmi | 20 | 7 | 13 |

2 | Boven Digoel | 20 | 6 | 16 |

3 | Asmat | 25 | 14 | 11 |

4 | Mimika | 35 | 18 | 17 |

5 | Fakfak | 20 | 8 | 12 |

6 | Raja Ampat | 20 | 9 | 11 |

7 | Sorong | 25 | 6 | 19 |

8 | Wondama Bay | 25 | 11 | 14 |

9 | Merauke | 30 | 3 | 27 |

10 | South Sorong | 20 | 3 | 17 |

11 | Jayapura City | 40 | 13 | 27 |

12 | Keerom | 20 | 7 | 13 |

13 | Jayapura Regency | 25 | 7 | 18 |

14 | Papua Provincial House of Representatives | 55 | 44 | 11 |

15 | West Papua Provincial House of Representatives | 45 | 17 | 28 |

|

|

|

|

|

'backward regions and people' is accompanied by a disrespectful valuation of their humanity. In extreme expressions, such as during the racial incidents of August 2019, any human dignity is denied, or rated very low. Moreover, since some fighters for 'liberation from oppression' chose to seek more serious attention by resorting to violence, fighters in Papua have been categorized as 'terrorists' (2021).

This is the result of years of 'stigmatization' that has never been challenged. With today's more sophisticated means of communication, the general public has access to many different sources of information. However, these sophisticated means are still systematically and structurally used by state organizations that organize campaigns to present inaccurate or incomplete information ('Open season', 3 August 2021). So the process of stigmatization continues. This stigmatization is also complemented by an effort to make consumers believe that there is no problem in Papua. Or, at least

that the government has gone to extraordinary lengths to develop the region - funneling huge budgets - while regarding all human rights. This type of campaign is occasionally encountered by 'communications monitors'. Certainly, the misinformation campaign on Papua, as reported r e c e n t l y by Harvard University ('A pro-government disinformation campaign,' October 19, 2022), has had a very negative impact and obscured understanding of the real conflict in Papua.

Such realities have also begun to prompt institutions such as the United Nations (UN) to address questions to Indonesia with greater frequency and clarity. At the end of 2021 the UN asked Indonesia to answer several very concretequestions ('UN letters RI,' February 12, 2022). Due to the lack of response from the authorities, the UN instead chose to open up the UN's questions to Indonesia, so that the entire international community could know about them. Also around the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) process by

UN High Commission on Human Rights, October 2022, many international organizations continued to complain about the incorrectness of much of the information officially presented by Indonesia to international forums ('Rejecting the Government's Claims,' 11 November 2022). In the same context, it has been repeatedly requested that the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights be allowed by Indonesia to visit Papua. Such requests have to date been formally accepted by Indonesia, but their effective implementation has been continuously blocked by Indonesia. For years, free access for journalists, both national and international, has been difficult to the point of de facto not being allowed. For what reason?

In relation to the issue of outgoing information, during the heated period following the August 2019 racial incidents, access to the internet in Papua was blocked by the Ministry of Communication and Information (Menkominfo). This action was not justified by the judges when the case was heard in court in Jakarta. They held that the President and the Minister of Communication and Information were guilty. However, in the course of the 'appeal' by the Minister of Communications and Information the decision was changed again, and it seems that in certain cases such actions can be carried out. Again a very concerning sign.

IMPACT ON PAPUAN LIFE

The developments described above have had a major impact on daily life in Papua. The impact of this 'strategy of total control and paralyzing political opponents' takes many forms. Some key aspects are highlighted below:

[1] The role of civilian government is gone

The first major impact can be felt at the level of policy determination in Papua. The party that determines all kinds of policies in Papua is not the provincial government or the DPRP, but the central government and its agencies. Civil government in Papua appears to be dysfunctional, with no notable innovative activities or public service programs

which really answer the needs of the wider community. What is most prominent is that in policy discussions it turns out that the security forces (TNI-Polri) are more decisive and regulate the daily lives of residents in Papua. The impression is that everything must be accountable to the 'security forces', and not to the Governor and his ministry.

This pattern of governance is still reinforced by the role of the BIN apparatus, which in recent years has strongly influenced and actively managed policy in Papua. In fact, they have not hesitated to promote and rely on organizations identified as 'radical nationalist' (e.g. Barisan Merah Putih) to control the direction of politics in Papua. They do not hesitate to circumvent other state institutions, such as the MRP, in order to carry out their duties. This was very evident during a series of evaluation meetings, particularly in Wamena and Merauke (November 2021). The role of BIN was also very evident, given that the decision to expand was based solely on BIN information, and not on s o u n d research into the opportunities for regional independence to improve the welfare of local communities.

[2] People are confused and polarized

Furthermore, it can be noted that the general public is increasingly confused by the situation as it stands. All of us,up and down the country, are spectators by the side of the road, and could in fact simply fall victim to a 'conflict resolution strategy' that solves nothing. That is scary, and makes many citizens ask: what about tomorrow? The number of people who have been victimized is already too many, including the 60,000 people who have been forced to flee, leaving their villages and food security behind. What about tomorrow? Who can you run to?

Of course, this reality is felt most keenly in the conflict areas themselves, and affects both, indigenous Papuans and

Non-Papuans. However, confusion is not limited to conflict areas. Also, in urban areas far from conflict areas, the impact of 'violent control' is felt in the form of loss of rights to freedom of opinion and opinion, freedom of assembly and in the form of easy criminalization of certain people or organizations. Moreover, the danger of polarization and the threat of horizontal conflict are beginning to be felt.

It is possible that to an observer who knows little about what is happening in Papua today, the cities he visits seem very calm and friendly. There is no sense of serious conflict. The towns show bustling traffic, shops are plentiful, trade is going on, and there are no incidents that a cursory glance would reveal. It is also likely that individuals or parties with economic interests and positions of some kind, evaluate the developments so far differently than individuals or parties who diligently follow developments in Papua both near and far from their homes. The assessment of a person who strives for a common life characterized by true justice and noble values, will certainly assess developments in Papua as very concerning. The benchmark: equal dignity of every human being, truth, honesty, justice, respect, togetherness, peace.

[3] living in discomfort

Actually, the public's confusion is quite large because they feel that life is uncomfortable. Moreover, during the year 2022, we were all shocked that violence could develop into killings that transcend all humanity, as happened in Timika in August 2022. Four people were mutilated, killed and dismembered and in a sack dumped in the river. Such events bring us to a standstill and a thousand languages. What is happening here? And how could such a thing have happened? It was even more alarming when Komnas HAM, after examining the Timika case, stated that "they have a strong impression that the perpetrators had committed killings like not for the first time ".

('Komnas HAM Suspected,' September 20, 2022). This conclusion is frightening. Not only in Timika, but killings of this kind have occurred elsewhere as well. The killings by the TNI through persecution in Mappi are no different (31/8/2022); or the killings by TPNPB of 8 telecommunication workers in Beoga, Ilaga district (2/3/2022); or by TPNPB of 10 civilians in Nogodaid, Nduga district (16/7/2022); or of 4 workers on the Trans Road in Maskona Barat, Teluk Bintuni district (29/9/2022); or the persecution of three children by the TNI in Kerom (8/11/2022). This is Papua/Indonesia anno 2022! Who can be expected to protect the people? Typically, the Governor is silent, and institutions such as the DPRP and MRP 'always seem to be in recess and inactive', except for one or two members.

[4] powerless institutions

The community normally expects institutions to help, but it turns out that from the DPRD to Religious Institutions, Customary Institutions or Non-Governmental Organizations, it also does not bring adequate calm. More and more institutions give the impression that they themselves do not know how to respond. The DPRD is usuallysilent, and seeks to be busy in formal and ceremonial matters, but which do not bring any improvement. The Papuan People's Assembly (MRP) is still vocal, but it turns out that it is not an institution that has power, so it is easily played with, becoming a 'decoration of democracy'. Religious institutions/churches are still partly vocal, but at the same time show an ambiguity of 'taking sides here and there'. In fact, a polarization between institutions or between members within institutions is increasingly visible as well. Polarization, pro and con, further weakens and paralyzes the power of civil institutions, including religious ones. There is ethnic polarization, there is religious polarization, there is polarization between citizens (elite - ordinary people), there is polarization of the pros and cons of the liberation struggle, there is polarization of the pros and cons of Otsus and DOB. In addition,

there is the impression that each institution tends to act and speak separately and shows little desire to join forces to strengthen its voice for the improvement of the situation in Papua.

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in general are still trying to respond to the developing situation. However, they too suffer from limitations, and their voices are easily ignored. Most prominent are NGOs working in the field of justice. In recent years they have been very active and have sought to join forces to 'go against the grain' to achieve justice for the voiceless. They also occasionally cooperate with 'legal aid' networks outside Papua, both national (e.g. YLBHI, Kontras,Haris Azhar) and international (e.g. Amnesty, Tapol). A number of NGOs in Papua working in the environmental field are also quite vocal, because they get help from NGO networks from outside Papua, (e.g. Mongabay, Walhi, Greenpeace, Yayasan Pusaka Bentala Rakyat) which are very competent and have the capacity, so it is easier to speak out at the local and national levels. Despite working to the best of their abilities and with great dedication, the 'NGO world' has not yet succeeded in pushing the authorities to change their ways. Instead, they risk being criminalized (examples: Haris Azhar and Fatia Maulidiyanti). Thus, 'a sense of powerlessness' is also a frequent companion of NGOs.

[5] prioritization of economic improvement patterns that do not favor indigenous peoples

All the confusion described earlier is also inseparable from the political prioritization exhibited by the current Jokowi-ledgovernment. Most notable is the priority given to 'economic development' above all else. The economy is number one. This choice of economic priorities means that all investor movements are specifically encouraged and facilitated. This is facilitated, for example, through the Job Creation Law/Omnibus Law, which reduces the opportunities for local communities to protect themselves and ensure that their traditional food sources

stay preserved. The ease of investment often clashes with the interests of local communities and with the imperative to protect the environment. Moreover, in protest movements against land grabbing and deforestation, communities are often confronted by security forces, losing and even being blamed or victimized.

Within this framework, it is also not surprising that it has been repeatedly pointed out that behind the operations of the security forces there are often other interests, namely economic interests. Compare the reporting around the gold mountain (Wabu Block) in the Intan Jaya region, and how the complainants were eventually brought to court (criminalized) for criticizing the government and security forces. Or the fact that a legal action at the district level can be overturned at a higher court level. For example: The Bupati of Sorong District, in line with the President's policy, revoked the operating licenses of a number of 'oil palm' companies. The companies sued the Regent at the StateAdministrative Court (PTUN) in Jayapura. The PTUN judge ruled that the Regent's actions were legal, and that the companies should abide by them. However, the Regent's decision was again overturned by the Administrative Court in Makassar during an appeal by the companies concerned. How can a community not be outraged and disheartened by this kind of injustice over and over again? Meanwhile, deforestation continues and this further results in the marginalization of local communities.

The impact of the mastery approach coupled with economic priorities is: the creation of an atmosphere of injustice, violence, and denial of the dignity of the Papuan people. And 'Jakarta' doesn't seem to have a headache!

[6] human rights violations with impunity

The atmosphere of life in Papua is also affected by the lack of resolution of cases of human rights violations, including gross human rights violations. Doubts about the courts, which have long been expressed by the community, have been strengthened once more in

late 2022 by a trial related to the Paniai gross human rights violations case (2014). This new trial was held at the Human Rights Court in Makassar. The conclusion: the trial was a charade that did not seek justice at all, nor did it bring the feeling that 'justice was done'. In the Paniai case, this reality was understood by relatives of the simple victims, so they refused to attend the proceedings.

The same can also be seen in the slow resolution of a number of very serious cases of human rights violations over thepast years. This includes the murder of Pastor Yeremias in Intan Jaya (Sept '20), which has been investigated by various Fact Finding Teams. Broadly speaking, all teams agreed that Pastor Yeremias was killed by the authorities and the name of the perpetrator was known. To date the court process has not been finalized.

The government has now decided to resolve a number of cases of gross human rights violations through non-judicial means. The goal is that all cases that have not been resolved for a long time will finally be completed by the end of 2022. In the official document establishing the non-judicial settlement program, the government explains that the focus of the settlement is on the families and relatives of the victims. The perpetrators are not the focus, and can be set aside; once again they walk free (Presidential Decree 17/2022, 2022). The extended families of the victims have rejected such a settlement. Indeed, the extended families of the Wasior victims made a series of demands for compensation, but also argued that justice was lacking. The impression is that any final settlement - a very rushed process - will be ineffective.

- just to appease the 'international community'

and not driven by a genuine and heartfelt motivation to seek the delivery of justice.

[7] sense of entering a dead end

The complexity of developments over the past 3 ½ years and their impact on people's lives in Papua is enormous and severe

until many people feel that we have entered a dead end. Where are the bright spots? Some people choose to play along until they feel safe, some people choose to give up and become spectators, some people still want to find a way, even though they feel that they will experience many obstacles and frustrations. While recognizing the enormous negative impact of the 'strategy of violent control' that has led us to a 'dead end', below we will still reflect on perspectives towards a way out, towards Papua the Land of Peace.

FORWARD-LOOKING PERSPECTIVE

The atmosphere created by the 'security approach' to resolving the conflict in Papua looks very bleak. As noted above, most people who care deeply about developments in Papua are losing hope and enthusiasm. Many have given up, and those who are still eager to fight for Papua to become "Papua the Land of Peace" are becoming increasingly desperate.

In general, it can be said that concerned parties are increasingly convinced that Papua can only enjoy peace if the true content of the conflict is revealed honestly and deeply. Only if all parties are willing to sit together in an atmosphere of mutual respect. The security approach has proven to be a complete failure. The tendency of both sides to absolutize their opinions, which are summarized in the handles "Papua Merdeka Harga Mati" (Independent Papua Not Negotiable)and "NKRI Harga Mati" (United Republic Indonesia Not Negotiable), will certainly not bring peace, but only suffering. Since the beginning of 2000 for a number of years there has been a spirit to initiate a genuine dialog, but that spirit was eventually lost because it was not supported by a true 'political will' to resolve the Papuan conflict with dignity. So, we ended up in an 'atmosphere of rampant violence', an 'atmosphere of stalemate', which severely paralyzed any spirit of moving together.

[1] Initiative of Komnas HAM

Recently, Komnas HAM has taken an initiative. However, this initiative is quite questionable. First of all, Komnas HAM was not given an official mandate from the President. Thus, this initiative is more of an internal ambition of Komnas HAM than an official move by the state. Secondly, some argue that Komnas HAM has so far failed to prove its neutrality and effectiveness. Many cases of human rights violations in Papua have not been properly resolved, thus not providing justice to the relatives of the victims of human rights violations. Thirdly, there is an impression that Komnas HAM's style of movement is somewhat colored by the 'show off' aspect, or in other words: showing the national and international community thatIndonesia has taken the conflict in Papua very seriously. Fourth, in its efforts to reach an 'agreement', Komnas HAM has also been less active in involving parties who are actually authoritative in Papua to participate in thinking about resolving the conflict. Fifth, Komnas HAM has occasionally chosen to cut corners and claim that it has succeeded. For example: the joint signing of the 'Humanitarian Pause' MoU (Nov 11, 2022), which actually did not involve the two most decisive parties in the armed conflict in Papua, TPNPB and TNI-Polri. The 'humanitarian pause' agreement was boasted and announced in Geneve. A side question: why do meetings leading up to the humanitarian pause need to be held in Geneva, and cannot be held inJayapura? Komnas HAM also claimed to have met with 'TPNPB leaders'. This was denied by the TPNPB, who explained that Komnas HAM met with 'fake leaders' (TNI-assisted leaders), making

were more of a step backwards, as it is likely to be a failure, as the important parties are not involved and there is no preparation on the ground. 4

Despite the de facto lack of support for Komnas HAM to date - for the reasons mentioned above - it may be possible for us all to use its initiative to initiate change. Komnas HAM should abandon its overweening ambitions and, together with other concerned parties in Papua, start looking for an initial path that could eventually lead to a dialogue. In this initial stage, Komnas HAM needs to be a listener until it begins to truly understand the complexity of the conflict in Papua. Then together with partners in Papua, it can focus first on 'restoring the atmosphere in Papua, that is, 'getting out of the stalemate'. Changing the atmosphere as described above is an absolute requirement for thinking about a dialog that has real substance.

[2] need to take a turn

From the outset we can note that with the developments over the past 3 ½ years, we have experienced a huge step backwards in the process of resolving the conflict in Papua. That realization means that we all need to acknowledge that the h i t h e r t o favored security approach has failed miserably, in terms of resolving the conflict in Papua. Such recognition is the first step towards an 'openness to conflict resolution'. The first thing we need, then, is: the willingness - the political will - to change course!

[3] Conflict resolution in Papua has two stages

the claim misleading. In its response Komnas

HAM stated that it was not yet time to reveal in detail who they had met with.

Anyway, the working style of Komnas HAM is still in doubt, and in fact there is an impression that the events surrounding the 'humanitarian pause' agreement

4 The "Humanitarian Pause" agreed in Geneva between Komnas HAM, ULMWP and MRP, is actually very limited in scope both geographically, in time and in its targets. This Humanitarian Pause will only be applied to the Maybrat conflict area, will be valid from December 10, 2022 to February 10, 2023 (2 months only) and aims to provide a safe opportunity to distribute aid to refugees and invite them to return to their villages.

Towards a dialog and/or towards a resolution of the conflict in Papua, we will face two rather different, but complementary stages, namely: [a] The first stage: How to eliminate the negative impact of the developments of the last 3 ½ years? And [b] Stage two: How to get back on track, i.e. a dialog based on a true breakdown of the main roots of the conflict in Papua? The result of the first phase is actually the preparation of the terrain, the fertile ground to enter the second phase.

PROPOSED FUTURE PEACE AGENDA

[1] restoring basic rights, trust and hope

In order to prepare the ground for a possible dialogue in the future, we are all called upon to help restore the gloomy atmosphere to light. In this process of restoration a number of aspects need to be given very serious attention, including the following:

· Refrain from all forms of violence in the form of armed contact; humanitarian pause in the broadest sense,

· Stop the process of militarization of the Papua region; withdraw many troops from Papua,

· Restore the constitutional right to freedom of expression in full,

· Stop all forms of stigmatization' stop all misleading campaigns,

· Create a space for precise and correct information; opening Papua to journalists (national and international) and to the UN Special Rapporteur;

· Treating all people equally before the law;

· Moving away from a 'state of control' in Papua, the Central Government needs to shift back to a 'state of law';

· Protecting activists fighting for human rights and the dignity of every human being;

· Postponing the implementation of the DOB plan; and restoring Autonomy in Papua;

· Controlling the influx of large numbers of migrants.

[2] Work agenda

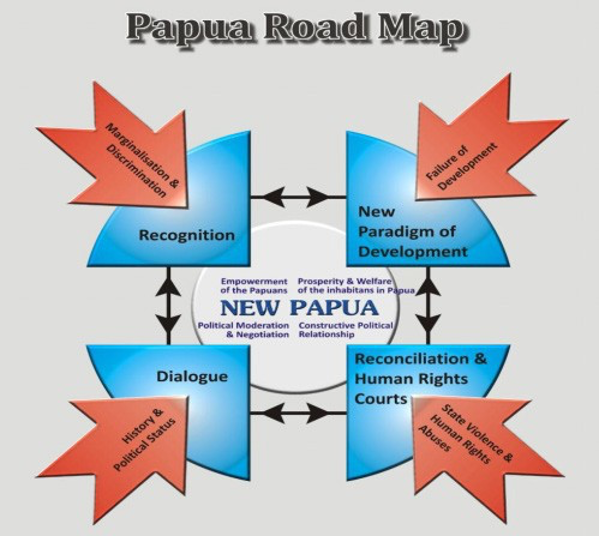

List of aspects (mentioned above) - can still be completed- could be an initial work agenda. We all need a "humanitarian pause" not only with regard to the plight of the refugees, but so that as a society at large we can breathe again in a relaxed and calm manner. We want a non-threatening atmosphere to look at all the problems that exist, because they are not few (just look at the list). Restoration of the atmosphere can be an initial work agenda not only for Komnas HAM but also for all institutions concerned in Papua, including, and perhaps even specifically, religious institutions. What we need now is a 'kitchen' where a number of 'chefs' from various organizations work together with one goal in mind: to resolve the conflict in Papua peacefully and with dignity. In that kitchen, a 'roadmap to Papua, the Land of Peace' is being reconstructed. The first part of the roadmap is: restoring some basic rights as well as trust and hope.

[3] 'political will' and shared responsibility

Conflict resolution is no longer just the responsibility of the central government, but our collective responsibility. "True political will" does need to be shown by all parties, especially the Central Government and its ministries. The government needs to give a meaningful mandate (as an expression of its political will) to its partners in Papua to restore a safe and secure living environment where there is no place for discrimination, marginalization, stigmatization, criminalization, and where the rights and dignity of everyone are fully recognized.

[4] This first stage needs to be executed immediately

If the current situation in Papua is not changed urgently, more and more observers are of the opinion that the situation will develop in a more violent direction. The use of violence from both parties - the self-determination fighters

as well as the security forces - will increase. More chaos and more victims will fall on this beautiful land ofCenderawasih. A report entitled "DON'T IGNORE US prevented mass atrocities in Papua, Indonesia” published by the "Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide" provides an analysis of the situation in Papua. The analysis iscomplemented by a description of atrocity scenarios that are likely to emerge over the next year to a year and a half(Supriatma, 2022). The following is the second phase

[5] entering sensitive terrain: 'mutual recognition'

Once out of the 'stalemate' described in the first stage of the process, we will have enough space to give full attention to the dialogue and its substance. Of course, the first thing that needs to be answered in this second stage is: what are the roots of the conflict in Papua? Answering that question we will realize that one of our greatest difficulties is that

until now we do not have a consensus on the substance of the conflict. Ask the Indonesian government what the root causes of the problems in Papua are, and the answer will revolve around economic issues, welfare and the identity of the Papuan people/nation. Whereas if you ask LIPI (now BRIN), they will point to research where it was found that there are four mainroots:

[a] discrimination/marginalization,

[b] inappropriate development patterns,

[c] history and political status, and

[d] human rights violations.

Ask an indigenous Papuan: the answer is about the history of its integration into the Indonesian republic, the history of the denial of his basic rights as a nation from then until now.

Of course, starting a dialog without a common understanding of the conflict can only result in a playful atmosphere, and will not end with a solution to be proud of. A consensus of shared understanding is absolutely necessary if we are to have a true dialogue. To this day it is still very difficult to reach this consensus. The most troubling aspect is the fundamental political aspect that is revealed in the

records of indigenous Papuans and those already recorded are also in LIPI's understanding where history and political status are alluded to.

INDIGENOUS PAPUAN PERSPECTIVE

[1] An Indigenous Papuan Perspective

Given that in this paper we are highlighting the situation in Papua specifically from the point of view of indigenousPapuans, it would be good to also try to explain the main roots as raised by the "first-born children of Papua". The root of theproblem in Papua is actually nothing other than the bitter experience of the indigenous Papuans as they experienced that their land and habitat were simply claimed by others. This bitter experience began with all forms of colonization that they experienced since the arrival of the Dutch who began occupying Papua. Their ancestral lands were seized as the property ofthe colonizers and their natural resources were seized and used as a source of wealth for the colonizers. The presence of the Papuan people as owners of the land is not recognized and their dignity is underestimated, considered below the standard of civilization. What is the basis for such actions? The Dutch may feel more entitled because of their white skin and/or feel smarter/superior? They think that the land is empty? The inhabitants seem to be ignored; why is that? This bitter experience is the root of all the problems in Papua today. This bitter experience continued during the administration of the Dutch government and during the administration of the Indonesian government.

It is not only the Papuan people who have gone through this very bitter experience. There are many similar examples. One example is in neighboring Australia, where the Aborigines were displaced from their position as the authentic owners of their land by the 'settlers'. And another example in New Zealand where the Maori nation suffered the same fate. Or the example of the Indians in America and Canada who have recorded the same bitter history.

Only slowly, course, over the past decades, the 'gravTeheo van den Broek

sins' of the past have begun to be realized and acknowledged by the 'old colonial powers'. The reality is now being revealed by 'apologizing for the sins of the past'. The most recent example is Pope Francis' 'pilgrimage of repentance' to Canada to apologize profusely to the Canadian Indians. Also the Dutch colonizers apologized to Indonesia for their 'violent colonial actions' during the 1940s. Slowly all the 'colonial powers' are coming to their senses and learning the lessons of this very sad and inhumane history.

[2] This is a familiar experience for Indonesians.

Looking at the context of the conflict in Papua, it is actually difficult to understand that Indonesia, which has gone through the same bitter experience, is not utilizing the lessons from its own history in the process of determining government policy today. Indonesia itself fought heroically against the invaders in the 1940s, because it felt that its identity and dignity were not recognized, but instead were stepped on by the Dutch and Japanese invaders. Why is this experience not carried over into the current policy as an 'independent state', 'Independent Indonesia' towards the Papuan people today? Today the Papuan people are experiencing the same thing as Indonesia almost a century ago. They too feel unrecognized and their identity and dignity trampled upon. Their land is visited by 'outsiders', in this case also Indonesians, and seized as if these 'guests' feel more entitled to own it. More entitled because of what, because they were smarter, or because their skin color was lighter, or because they thought that the results of the PEPERA 5

5 PEPERA (popular vote) was a referendum for the Papuan people to declare whether or not they wanted to join the Republic of Indonesia. The Indonesian government was obliged through the provisions of the New York Agreement (August 15, 1962)

- which provided for the transfer of government administration from the Dutch to the Indonesian government - to hold a referendum based on the principle of 'one man, one vote' no later than 1969. Indonesia

meet the standards of true justice? We all know and can realize that the 1969 PEPERA was a process that systematically and structurally rejected all free participation by the Papuan people, so that this PEPERA was very legally flawed. This fact wasalso recognized by the UN Plenary Meeting when they 'archived' the results of the PEPERA as 'having taken note', but they very much avoided stating openly that they considered the results of the PEPERA to be a legitimate expression of Papuan opinion. The point is, of course, that even in the exercise of the democratic process of expression of opinion, the 'rights of the first-born Papuans' were denied, and their dignity was severely undermined.

[3] political action 2020-2022

Today the 'atmosphere of not being recognized for their identity and dignity' is still very much felt by indigenous Papuans. In particular in the whole process such as the ratification of both the Special Autonomy Law Volume II and the Papua DOB Law. As in the past, everything was done without hearing the voices of hundreds of thousands of Papuans. The right to express their opinions peacefully was effectively eliminated by forcibly dispersing all demonstrations. In fact, during the preparation stage of the demonstrations, organizers and volunteers (such as those distributing invitation sheets) have beenarrested and taken to police headquarters for interrogation and intimidation. There has been no openness at the central government level to move away from a strategy of control, and this reality has a major impact on the situation in Papua in 2022.That is the problem and the main root of the Papuan conflict, and such conflicts can never be properly resolved through a control approach.

[4] There is no meaningful dialog if it does not address the political aspects of the Papuan conflict!

abandoned that principle and unilaterally selected and directed just 1026 Papuans to ensure that they were 100% in favor of integration into the Republic of Indonesia.

In other words, only an open dialogue that gives due place to the 'political aspects' described above has a chance of success. A dialogue characterized by recognition of everyone's dignity, mutual listening and respect, can clear the way to a solution of which we can be proud. Recognizing that until now the 'main problem', which is indeed a 'political problem', has been given less priority in the search for a solution to the conflict in Papua, there can be hope that the Government will finally get its act together. This key step will receive support, not only from Papuans. But also support from Indonesians who have come to realize that the problem in Papua is not something created by indigenous Papuans,but is a problem created by their history with Indonesia. This is a 'man- made' problem and the solution must also be 'man-made'. Human beings who are aware and equally convinced that we exist in this world to create space and hospitality for one another with equal rights, dignity and life.

CLOSING

We are very interested in the notes of a former Minister of Law and Human Rights of the Republic of Indonesia, Hamid Awaludin, in his opinion published by Kompas (Awaluddin, 5 Janauri 2023), entitled 'Humanitarian Pause in Papua', where he notes: "What is the continuation of peace efforts in Papua? In any vertical domestic conflict, including Aceh, the government should always take the initiative to start looking for ways to bring about peace. Of course, some people think that taking the initiative means that the government is giving in to the resistance groups. Taking the initiative is about winning the battle, which is about realizing peace. The end of a war is peace. This perspective should be held by the government in addressing Papua. Egos must be set aside". Therefore, we all need to be brave for the sake of humanity.

Theo van den Broek

LITERATURE

Amnesty International Indonesia. (2020, November). Amnesty International And The Alliance of Independent Journalists. Report Submission To The 41st Session Of The UPR Working Group

Awaluddin, H. (2023, January 5). 'Humanitarian pause in Papua. ' Kompas Daily Opinion page

7. Accessed from Humanitarian Pause in Papua - Kompas.id on 7 Janauri 2023.

Institute for Policy Analysis and Conflict (IPAC). (2021). Diminished Autonomy and the Risk of New Flashpoints in Papua. IPAC Report No.

77. Jakarta: IPAC.

IPAC. (2022). Escalating Armed Conflict and a New Security Approach in Papua. Jakarta: IPAC.

Komnas HAM Suspects Mutilation Suspect in Mimika Did the Act More Than Once' (2022, September 20). Accessed fromhttps://nasional. tempo.co/read/1636481/komnas-ham- suspects-mutilation-suspects-in-mimika-did- the-axis-more-than-once onDecember 2, 2022.

Rakhman, O., Ma'rafuh, U, Kausan, B.Y & Ardi. (2021). The Political Economy of Military Deployment in Papua, The Case of Intan Jaya.Jakarta: #Bersih- kanIndonesia, YLBHI, WALHI Executive Nasi- onal, Pusaka Bentara Rakyat, WALHI Papua, LBH Papua, KontraS, JATAM, Greenpeace Indonesia, Trend Asia.

State Secretariat. (2022, August 26). Presidential Decree No. 17 of 2022 on the Establishment of a Team for the Non-Judicial Resolution of Past Gross Human Rights Violations.

Supriatma, MT (2022, July 19). "Don't Abandon Us": Preventing Mass Atrocities in Papua, Indone- sia. Washington DC: The Simon- Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

van den Broek, T. (2020). DEMAND DIGNITY,

PAPUA GUILTY, A Portrait of the Politics of Racism in the Land of Papua 2019. Passionist Memo- ria Series No. 38. Jayapura: Secretariat of Franciscan Justice, Peace, and the Integrity of Creation in Papua.

Widjojo, M. S., Elizabeth, A., Al Rahab, A., Pamung- kas, C., & Dewi, R. (2010). Papua road map: Negotiating the past, improving the present, and securing the future. Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia.

Internet Source:

'A pro-government disinformation campaign on Indonesian Papua.’ (2022, 19 October) hks. harvard.edu accessed from https://misinforev-iew.hks.harvard.edu/article/a-pro-government-disinformation-campaign-on-indonesian-papua pada 2 Desember 2022

--------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.